In the previous part we witnessed the early development of full colour printing, most likely a private business to begin with, as well as the standardization of print formats by the upcoming commercial publishers – resulting in a standardization of both printing blocks and paper sheets – so as to make these prints at last into a viable commercial business. Essentially this also meant finding cheaper and simpler kinds of paper that wouldn’t require so much dampness as the luxurious soft and thick hōsho paper from Echizen Province, Echizenbōsho 越前奉書, so as to more easily absorb the pigments, as well as enabling a much more efficient printing process as the printed sheets would also dry more quickly.

The period of 1794 to 1825 for this instalment may seem to be chosen somewhat haphazardly. Yet it corresponds exactly with the period when Utagawa Toyokuni 1769-1825 歌川豊國 was active in the genre of prints of actors, also including the work of his early pupils, such as Kunimasa 國政, Kunihisa 國久, Kuninaga 國長, and many others. We should also realize that Toyokuni was one of only two artists who managed to survive and overcome the changes in the world of prints in the 1790s, adapting without any problem to what a new audience expected. Thanks to both the flowering economy and the circumstance that prints could now be offered at much more modest prices as a result of the much more efficient production process – as we saw above – the commercial publishers managed to address a much wider audience. And Toyokuni understood very well that he was then catering to an audience that was very different from the kabuki aficionados for whom the Katsukawa 勝川 had worked from 1764 and he himself as well from 1794. From 1798 onwards, it again became customary to inscribe the names of the actors and the roles they played on the print – as had been the practice in the period of urushie 漆絵 and benizurie 紅摺絵 prints – thus assisting the many buyers who had maybe not even seen the play, or didn’t really know the plot, or even wouldn’t be able to identify the actor from his crest – indeed, a very very different audience from the members of the fan clubs of actors who bought the prints made by the Katsukawa artists. (The other artist who managed to survive the change of the audience from the late 18th century into the 19th century was Hokusai 北斎, who always kept reinventing himself and addressing new audiences. Kiyonaga 清長 was sort of happily retired, and Utamaro 歌麿 failed to adapt and simply had to give up printmaking, and Eishi 栄之, being of samurai descent, would focus on painting rather than designing popular prints.)

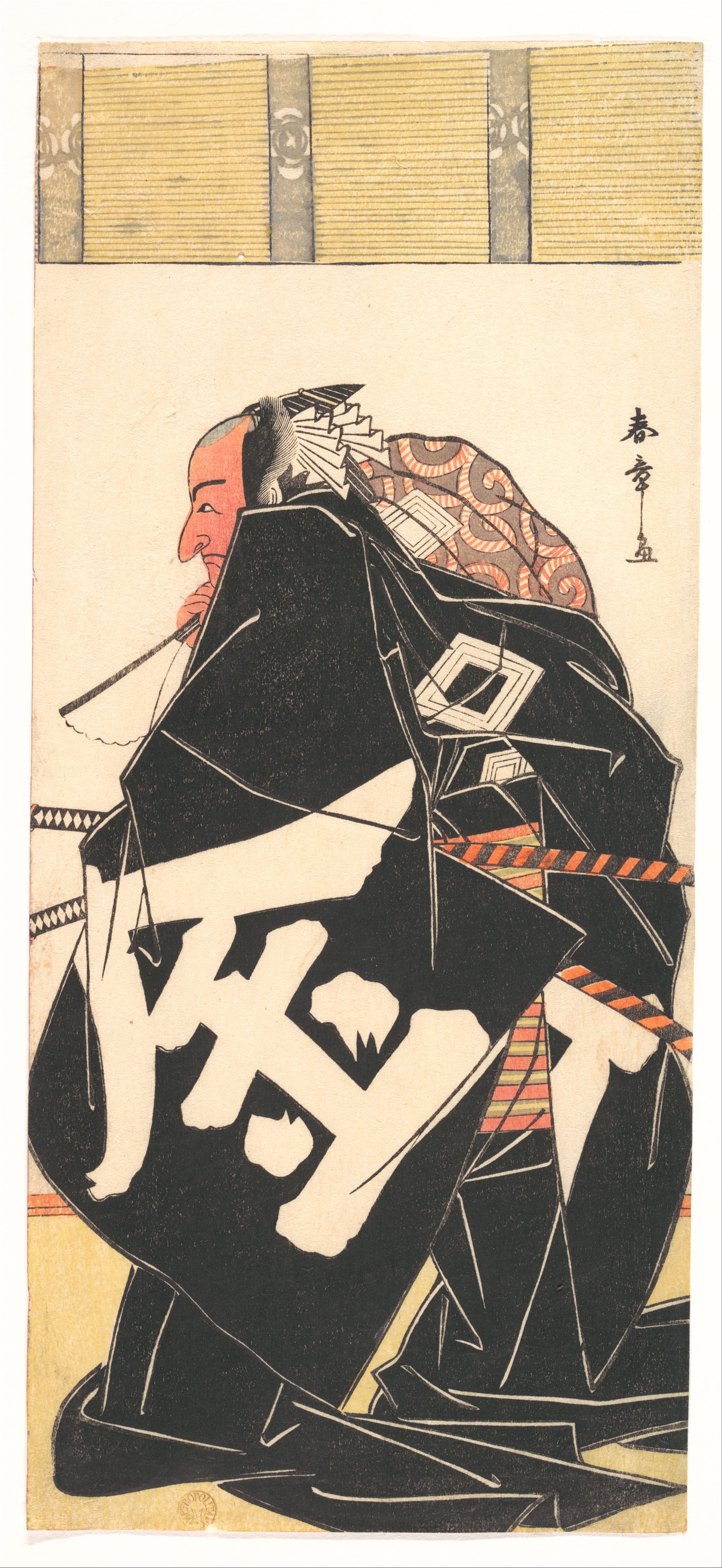

We know of a Toyokuni print portraying the actor Nakamura Nakazō as Ishikawa Goemon 中村仲蔵の石川五右衛門 after a performance in XI/1788 (listed in Fujisawa Akane, Utagawaha no ukiyoe to Edo shuppankai. Tokyo: Bensei shuppan, 2001, 322 [藤澤茜『歌川派の浮世絵と江戸出版界』東京:勉誠出版2001] and KN 5:69), but his real debut as a designer of actor prints was his series of Portraits of Actors on Stage, Yakusha butai no sugatae 役者舞台之姿繪 – you see, sugatae 姿繪, not yakushae 役者絵 — issued from 1794 by Izumiya Ichibei 和泉屋市兵衛, 52 designs known and an immediate success. Toyokuni’s first four prints in the series, one after a performance in the first month of 1794, two after a performance in the second month, and one after a performance in the third month, could well have been the talk of the town as they were released. And, as Roger Keyes suggested, this might have triggered Tsutaya Jūsaburō 蔦屋重三郎 to come with his reaction, in the form of his embracing the totally unknown artist going by the name of Sharaku 冩楽. Anyway, although we weren’t around then, it is certainly not impossible. On the other hand, it is quite obvious that this series of prints inspired Katsukawa Shunei 勝川春英 to design nineteen full length portrayals of actors against a soft grey ground after performances of the Chūshingura 忠臣蔵 drama at the Miyako Theatre 都座 in the fourth month of 1795 (KN 5:192, also see The actor’s image, 132).

As for the formats of Toyokuni’s prints when he was obliged to cater to the new audience of print buyers, there is a number of hosoban 細判 designs in the late 1790s and the early 1800s, but it is even more interesting to see a number of ōban diptych 大判二枚続 compositions from 1804, and a first ōban triptych 大判三枚続 in 1808. And this was only the beginning: from about 1815, the majority of Toyokuni’s prints of actors are ōban diptych and triptych compositions, and from the 1820s single prints are definitely a minority — this on the basis of Fujisawa Akane who records 810 prints of actors by Toyokuni and many more by other members of the Utagawa tradition. This also reflects the economic flowering of the Kasei 化政 period, as the Bunka-Bunsei Period (1804-30) is also known.

What we also see is that most of these diptychs and triptychs and occasional tetraptychs and pentaptych composition are largely preserved complete: the print buying audience was no longer comprised of members of the fan clubs who just wanted that one sheet where his or her favourite actor was portrayed. And probably the group of commercial publishers that then controlled the market wouldn’t have allowed such, now that the price of a complete triptych was probably less than one sheet of any Katsukawa polyptych at the time. Let’s now have a look whether the first and following positions are still similar to what we saw with the Katsukawa.

| Months | What | I | II | III | IV | V | VI | VII | VIII | IX | X | XI | Prints |

| 1697 1760 | tane urushie | 42% | 9% | 5% | 29% | 563 99.5% | |||||||

| 1742 1769 | benizurie | 27% | 9% | 9% | 5% | 6% | 35% | 854 100% | |||||

| 1764 1796 | Katsukawa Bunchō Sharaku | 17% | 6% | 6% | 7% | 9% | 6% | 40% | 794 99.5% | ||||

| 1794 1825 | Utagawa Toyokuni and pupils | 14% | 18% | 5% | 10% | 13% | 6% | 12% | 13% | 1284 98.5% |

No, this is now a very different story. What happened? First, second, third, and fourth positions were then taken by the months XI, I, VII, V, and II/III/VIII together, and now, in the years from 1794-1825, we are looking at III, I, VII/XI, IX, V, VIII and IV instead. New are IV with 5% and IX with 12%. So the prominent position of the first and eleventh months that took 71, 62, and 57% of the annual production respectively, is down well below the 50% mark, now accounting for a mere 27%. The relative popularity of the second month in the two previous periods was apparently to be short-lived. But in this period there are only three months, the second, sixth, and tenth, that fail to reach the 5% limit. Moreover, with no real difference between the 14 and 13% for the first and eleventh months, we cannot any longer speak of some clear preference.

Anyway, this means that prints of actors are from now really a commodity for all seasons. And this quite an accomplishment, realized in a period of some three decades – of admittedly a great economic prospering – for which both Toyokuni and the commercial publishers deserve all the credit. Toyokuni also quite generously gave his pupils a fair chance to make their way in the field, Kunimasa 國政 from 1795, by his contemporaries jokingly said to be rather the teacher than the pupil of Toyokuni, Kunihisa 國久 from 1804, Kuninaga 國長 from 1804, Kuniyasu 國安 from 1808, Kuninao 國直 from 1810, Kunisada 國貞, probably his greatest student and the most successful artists of the nineteenth century, from 1811 (represented by 265 prints of actors in this period), Kuniyoshi 國芳 from 1815, Kunikane 國兼 from 1823, and, always somewhat mysteriously, Toyokuni II 二代豊國 only from 1823, two years before Toyokuni’s death.

Coming back to my earlier remarks on the formats of prints of actors in this period, more specifically the development of an increasing number of diptych and triptych compositions, these are quite different from what we saw with the Katsukawa artists in the latter decades of the eighteenth century. Rather than representing actors on stage against a typical theatre décor, the actors in Toyokuni’s prints are more and more portrayed in some imaginary scenery rather in tune with the plot of the play, giving rise to often quite dramatic scenes that naturally appealed to the audience of the time, but could never be realized just using the common décor and stage props. This will undoubtedly have contributed considerably to the popularity of these prints. But we should also realize that we are here far from ‘actor prints,’ certainly when you would like to call them yakushae, these are in fact ‘kabuki prints,’ prints after kabuki performances in the theatres of Edo. Indeed, for true prints of actors, one would, interestingly, have to go to the Kamigata where this genre of prints survived easily until about 1830.

Anyway, Toyokuni also ensured that the field of prints of actors would from his days belong to the Utagawa tradition, and to the Utagawa tradition alone, Utagawa Kunichika 國周 probably being the last and certainly a most gifted and innovative artist. But how exactly they fared, we’ll see in the next part.